Assignment 3 – Part 1: Evidence of Completion of Four Different Course Activities

Click here to see a Google Doc that holds links to all four activities along with explanations and connections to the course resources and learning outcomes.

Assignment 3 – Part 2: Updated and Revised Blog Post

Here are the links to my three blog posts from #EDCI339.

I have chosen to update and revise my third blog post. You can find the revisions to the old post as a Google Doc here. It includes visual evidence of changes to the post in green and connections to the course learning outcomes highlighted in red. Enjoy the newly revised Blog Post #3 below!

Upon reflection on this week’s readings and blog questions, I have created a Sketchnote that demonstrates my initial ideas and thoughts on the topic.

In his piece for Monash University, Selwyn discusses how online education is now more than ever “taking on a more prominent role” as school systems navigate education during a global pandemic (2020). This means that all students need to have equitable access to their learning and we as educators must know how to provide that for them. We must teach the whole child and take into account all of their previous learning experiences that make them unique. Making sure learners have resources that represent them (what they look like, what their family looks like, their gender identity, race, ethnicity, heritage, culture, etc.) is crucial to their comfort and psychological safety in the classroom.

“Equity-oriented design in open education” by Kalir (2018) brings forward four design principles for educators to follow when creating and facilitating open “computer-supported collaborative learning” (CSCL) resources (p.4). This article connects with other readings this week in how it discusses ways for open learning to become more accessible for all educators and learners. I love how the article approaches these principles from an educator standpoint and shows ways for us to connect with each other. Check out the infographic that I created on Canva to summarize the proposed tactics.

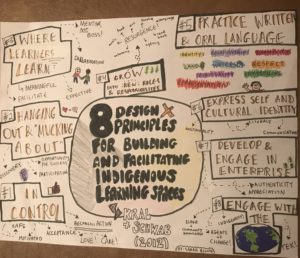

Of the required readings this week, I particularly enjoyed “Design Principles for Indigenous Learning Spaces” by Kral & Schwab. This piece identifies eight design principles for “building or facilitating [Indigenous] learning spaces” (2012, p.58). Click here to listen to an audio file where I speak about these principles based on the sketchnote below. Here is the transcript for that audio file accompanied by citations and references.

Universal Design for Learning needs to be woven into all equitable systems of learning. In their article, Basham et al. reflect on UDL and how it can help all learners when implemented properly into online education. While UDL was initially created as a technique for including learners with diverse learning designations and special needs into the “typical” classroom, it is now being used as a way to include all students and their unique variabilities (Basham et al., 2018, p.477).

The “three core principles” of UDL (multiple means of engagement, multiple means of action and expression, and multiple means of representing information) are used to “address the academic, social, and cultural distinctions that exist in today’s schools” (Basham et al., 2018, p.480). UDL aligns closely with the ideologies behind open and distributed learning because of its focus on “harnessing technology and instructional practices to remove barriers in curricula and across digital as well as physical learning environments” (Basham et al., 2018,p.480). Interestingly, the results of UDL in brick and mortar schools looks vastly different to that in open and distributed learning contexts. To learners with “disabilities, cultural impoverishment, and ELLs,” there are often “insurmountable barriers” present due to the “inaccessible rigidity of online learning materials and practices” (Basham et al., 2018, p.479). By making sure that online resources are personalized and student-centred, UDL guidelines can often be met (Basham et al., 2018, p.489). Every year, educators and school systems are becoming more and more “knowledgeable of the importance of addressing the diversity in today’s digital environments,” because of this, access and equity have also increased; however, we still have work to do (Basham et al., 2018, p.492).

While this article provides research-based evidence on UDL in open and distributed learning environments, I have a question for practicing educators today. What are some tried and true, effective methods of online instruction involving UDL that can be used to make the world of open and distributed learning more accessible and equitable for all learners?

To conclude this blog post, I will be sharing an interview that I conducted with a local Educational Assistant here in Victoria, BC. Allie Szwender works with grade four and five students and helped her class transition into online learning this spring. I wanted to learn more about her thoughts on the subject of equitable access to authentic, meaningful, and relevant open learning environments both in the classroom and online. Click here to listen to the interview or enjoy the Sketchnote below to view the highlights of the conversation.

Bottom reads “Any question is allowed if you are willing to learn from it.”

References

Basham, J.D., Blackorby, J., Stahl, S. & Zhang, L. (2018) Universal Design for Learning Because Students are (the) Variable. In R. Ferdig & K. Kennedy (Eds.), Handbook of research on K-12 online and blended learning (pp. 477-507). Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Mellon University ETC Press.

Canva (2020). Design Anything. Retrieved from https://www.canva.com/

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Kalir, J.H. (2018), “Equity-oriented design in open education”, International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, Vol. 35 No. 5, pp. 357-367. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-06-2018-0070

Kral, I. & Schwab, R.G. (2012). Chapter 4: Design Principles for Indigenous Learning Spaces. Safe Learning Spaces. Youth, Literacy and New Media in Remote Indigenous Australia. ANU Press. http://doi.org/10.22459/LS.08.2012 Retrieved from: http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p197731/pdf/ch041.pdf

Selwyn. N. (2020). Online learning: Rethinking teachers’ ‘digital competence’ in light of COVID-19. [Weblog]. Retrieved from: https://lens.monash.edu/@education/2020/04/30/1380217/online-learning-rethinking-teachers-digital-competence-in-light-of-covid-19

The “three core principles” of UDL (multiple means of engagement, multiple means of action and expression, and multiple means of representing information) are used to “address the academic, social, and cultural distinctions that exist in today’s schools” (Basham et al., 2018, p.480). UDL aligns closely with the ideologies behind open and distributed learning because of its focus on “harnessing technology and instructional practices to

The “three core principles” of UDL (multiple means of engagement, multiple means of action and expression, and multiple means of representing information) are used to “address the academic, social, and cultural distinctions that exist in today’s schools” (Basham et al., 2018, p.480). UDL aligns closely with the ideologies behind open and distributed learning because of its focus on “harnessing technology and instructional practices to

It is also an “intentional design” that builds up learning opportunities for

It is also an “intentional design” that builds up learning opportunities for

ibilities to learn from other viewpoints” by understanding that while another person’s views may differ from one’s own, those views are still legitimate and worthy (2006, p.496). PenPal Schools offers an opportunity to listen and share with friends across the globe and develop those conversations into collaborative projects involving both students’ new learning and their pre-existing viewpoints. A teacher, Jillian W., supports this by stating that “students [connect] globally on PenPal Schools to collaborate and learn together” (Common Sense Education, 2019).

ibilities to learn from other viewpoints” by understanding that while another person’s views may differ from one’s own, those views are still legitimate and worthy (2006, p.496). PenPal Schools offers an opportunity to listen and share with friends across the globe and develop those conversations into collaborative projects involving both students’ new learning and their pre-existing viewpoints. A teacher, Jillian W., supports this by stating that “students [connect] globally on PenPal Schools to collaborate and learn together” (Common Sense Education, 2019). Tying digital multimedia tools into PjBL allows students to “comfortably engage with the process of designing and developing their project” and being able to easily share and document their creations in “a digital format” (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.272). For elementary ages, PjBL improves “experiential reasoning and comprehension of relations,” content knowledge and group work skills, motivation, positivity in the classroom, and literacy (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.269-270). PenPal Schools is an effective tool for the implementation of PjBL into any classroom.

Tying digital multimedia tools into PjBL allows students to “comfortably engage with the process of designing and developing their project” and being able to easily share and document their creations in “a digital format” (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.272). For elementary ages, PjBL improves “experiential reasoning and comprehension of relations,” content knowledge and group work skills, motivation, positivity in the classroom, and literacy (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.269-270). PenPal Schools is an effective tool for the implementation of PjBL into any classroom. Learning about different countries around the world allows students to gain a better understanding of humanity and appreciate the similarities and differences between one another. The goal of globalized education, and PenPal Schools, is to form “a greater understanding of interconnectedness between self and world, skills and values” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.31). By connecting with other cultures, students can learn to empathize with others and work towards “sustainable development and peaceful societies” (Schweisfurth, 2006, p.42). PenPal Schools makes it easy for teachers to integrate global awareness into their classrooms by increasing their “global content,” “[supporting] the idea of student-perceived awareness,” and “[encouraging] student connections” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.28). While global citizenship may not be a concrete part of the BC Curriculum, teachers must integrate PenPal Schools or other similar multimedia technologies to work towards a more inclusive world.

Learning about different countries around the world allows students to gain a better understanding of humanity and appreciate the similarities and differences between one another. The goal of globalized education, and PenPal Schools, is to form “a greater understanding of interconnectedness between self and world, skills and values” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.31). By connecting with other cultures, students can learn to empathize with others and work towards “sustainable development and peaceful societies” (Schweisfurth, 2006, p.42). PenPal Schools makes it easy for teachers to integrate global awareness into their classrooms by increasing their “global content,” “[supporting] the idea of student-perceived awareness,” and “[encouraging] student connections” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.28). While global citizenship may not be a concrete part of the BC Curriculum, teachers must integrate PenPal Schools or other similar multimedia technologies to work towards a more inclusive world.

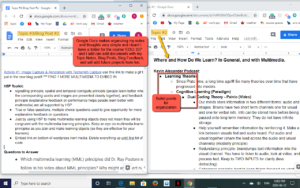

objectives require different visual formats. Initially, the purpose of static illustrations is examined and it is found that “adding static diagrams or illustrations to a verbal (text or audio) presentation frequently facilitates a deeper understanding of the to-be-learned material” (Butcher, p.181). An article by Kari Jabbour (2012) supports this claim by investigating the types of graphics that foster deeper levels of learning. For example, decorative graphics are often “used to inspire instructional display by adding artistic appeal or humor, but [have] no real instructional target” (Kari Jabbour, p.13). When incorporating graphics in a lesson, it is critical to eliminate unnecessary information and have an equal balance of text and visuals.

objectives require different visual formats. Initially, the purpose of static illustrations is examined and it is found that “adding static diagrams or illustrations to a verbal (text or audio) presentation frequently facilitates a deeper understanding of the to-be-learned material” (Butcher, p.181). An article by Kari Jabbour (2012) supports this claim by investigating the types of graphics that foster deeper levels of learning. For example, decorative graphics are often “used to inspire instructional display by adding artistic appeal or humor, but [have] no real instructional target” (Kari Jabbour, p.13). When incorporating graphics in a lesson, it is critical to eliminate unnecessary information and have an equal balance of text and visuals. Instructional Design and the importance of understanding your unique learners. Shah & Khan (2015) support this idea by stating “multimedia [tools] provide a variety of learning styles at the same time to cater to the requirements of different students” (p.350). Butcher summarizes the findings of multimedia visual and auditory stimuli options through the following benefits: simplifying visuals using well organized semantic models, integrating verbal and visual information both abstractly and concretely; using necessary animations/cues/spotlights, considering existing knowledge for connection making, and allowing students to create their own representations when possible (Butcher, p.194-195). Upon reflection on these findings, the implementation of multimedia in the classroom appears to be a viable option for student success. Through the use of multimedia tools, “learners become active participants in the teaching and learning process instead of being passive learners” (Shah & Khan, p.356).

Instructional Design and the importance of understanding your unique learners. Shah & Khan (2015) support this idea by stating “multimedia [tools] provide a variety of learning styles at the same time to cater to the requirements of different students” (p.350). Butcher summarizes the findings of multimedia visual and auditory stimuli options through the following benefits: simplifying visuals using well organized semantic models, integrating verbal and visual information both abstractly and concretely; using necessary animations/cues/spotlights, considering existing knowledge for connection making, and allowing students to create their own representations when possible (Butcher, p.194-195). Upon reflection on these findings, the implementation of multimedia in the classroom appears to be a viable option for student success. Through the use of multimedia tools, “learners become active participants in the teaching and learning process instead of being passive learners” (Shah & Khan, p.356).